Editor’s note: The text below is retrieved (“reblogged”) from at least two Tumblr users1 who have expert knowledge in the matter. Edited for clarity, readability.

Gender and Sex

… are both human made constructs designed to describe natural phenomenon but are not actually based in any biological reality. Much like the concept of “species”, it’s a model, and no model is an actuality—then it would not be a model, it would be a fact.

In truth sexual characteristics are diverse and varied and do not always match up with sex chromosomes; also, a sexual “binary” of sorts is not constant amongst all living things, and most organisms have other systems of reproduction.

Furthermore, gender is the suite of societally-defined social roles and behavioral characteristics that is typically assigned based on the externally perceived sex of a child; and does not actually have anything to do with biology—even less so than sex. Even though it is assigned based on this externally perceived sex, a person’s gender does not have to remain with the one assigned; much as we don’t determine people’s careers based on who their parents were anymore, your birth has no limitation on who you are and what gender identity you construct for yourself. Since it is a societally defined construct, people can and do construct more than the two traditional ones, and all are valid.

According to Principle 3 of The Yogyakarta Principles2, “Each person’s self-defined sexual orientation and gender identity is integral to their personality and is one of the most basic aspects of self-determination, dignity and freedom.”

That said, just because you cannot handle your societally constructed worldview surrounding sex, gender, and genetics being dismantled by sociology & biology itself doesn’t mean, additionally, that you have the right to make other people feel unsafe and uncomfortable—in short, that you have the right to remove people from moral consideration—simply because you don’t like having your world view being dismantled. Believe it or not, the complexities of human behavior & the diversity of sex and reproduction in life cannot all be covered in a simple high school biology class.

Simply put: There are more than two genders.

Identification

It comforts people to have a label applied to their gender especially since it often conveys their gender faster and more accurately than trying to describe the traits yourself, and it gives them a community and an identity that they were denied by traditional society.

In addition, it helps for people to agree with it because it costs someone a lot less to modify their worldview to include nonbinary genders than it does for someone who identifies with a nonbinary gender to reject their identity.

We have a strange culture on the internet that you ARE your opinions when that is not true. Your opinions should be an addon, an accessory to who you are; not a core part of your identity. Because your opinions can, in fact, be wrong—not all the time, but they can, and you shouldn’t cling to them.

You should be open to change, to understanding, to learning more about the world. And your worldview, your opinion, does not have precedence over someone else’s comfort and happiness. And people who identify as nonbinary genders can feel extensive dysphoria, pain, and suffering when they are forced to identify as something other than their chosen gender identity; a person having to keep their opinion about that to themself or changing their opinion to accommodate that is not as painful as the other person having to deny their identity. Because your opinion about nonbinary genders isn’t your identity.

People who identify as nonbinary genders aren’t hurting themselves, they aren’t hurting others, and thus it is not up to you to change them.

Examples, etc.

In school they teach you a very clean, concise, definitive way of doing things and you’ve probably learnt something like, “The definition of a species is a population of organisms that are able to reproduce and produce viable offspring,” or something. But anyone who has done even undergrad biology can tell you that that statement is incredibly reductive and incredibly controversial in the scientific community34

In fact, you probably don’t even need a background in biology to spot the obvious flaw in the logic there, which is the fact that organisms classified as different species do reproduce and produce viable offspring. Quite a lot, actually. Lions and tigers (Panthera leo and P. tigris), coyotes and grey wolves (Canis latrans and C. lupus)… In fact, there’s even a word for new species arising through hybridisation between existing species: hybrid speciation. 5

The great skua (Stercorarius skua) is believed to be an example of this in animals,6 and another interesting one that may be hybrid speciation in action (though not nearly anything that can be called a new distinct species yet) is the so-called “Eastern coyote”, a population of wild coyotes in the eastern US that are mixed with grey wolf and domestic dog, and can contain as much as 40% non-coyote DNA.7

And, in fact, the ability of two organisms to reproduce and produce viable offspring actually has very little with how we choose to classify them, because evolutionary and genetic relationships are rarely that simple. For example, some species that are the same genus - e.g. horses (Equus ferus) and donkeys (Equus africanus) can interbreed, but their offspring are usually sterile,8 while other species that are different genera to each other can interbreed to produce intergeneric hybrids, some of which are even fertile (for example crosses between false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) and bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus),9 or between king snakes (genus Lampropeltis) and corn snakes (genus Pantherophis).10

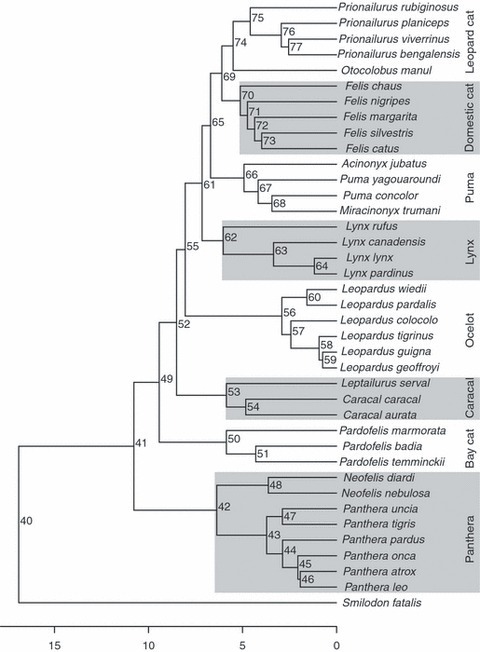

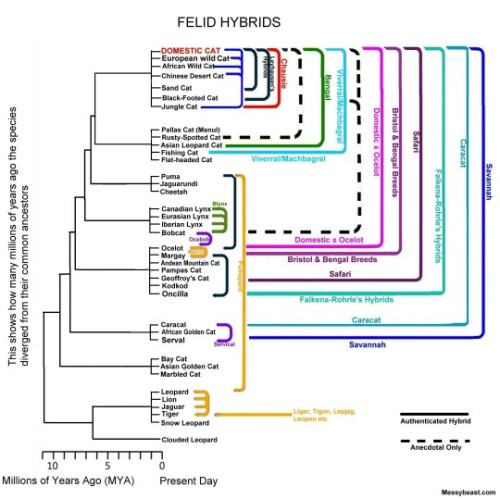

Most “exotic” domestic cat breeds (e.g. Bengals and Savannahs) also fall into this category - for some reason felids are genetically Weird in that a wide variety of species in the family Felidae seem able to interbreed with each other, no matter how different or distantly related they are.

Look at this. Now bear in mind that the domestic cat (Felis catus) is known to be able to interbreed with species in the caracal, ocelot, lynx and leopard cat lineages in addition to those in its own lineage, and if that wasn’t bad enough puma/leopard hybrids are a thing that exist. Those species aren’t even in the same subfamily, let alone genus or genetic lineage - the leopard is classed as subfamily Pantherinae, genus Panthera (P. pardus) while the puma is classed as subfamily Felinae, genus Puma (P. concolor).11

Although these aren’t even the most distantly related species that are able to interbreed. Domestic chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) are known to hybridise with guineafowl and the offspring of these crosses are interfamilial hybrids, since chickens and guineafowl are classified in different families (chickens belong to family Phasianidae, guineafowl to family Numididae).12

And of course another place where the “able to interbreed and produce viable offspring” definition falls apart is with organisms that reproduce asexually or without the need for a sexual partner, which is even more complicated when you consider that some species—e.g., some species in the paraphyletic whiptail lizard genus Cnemidophorus—are dioecious, meaning they have separate sexes, and reproduce by producing gametes via meiosis, but have actually lost the ability to reproduce sexually somewhere along the evolutionary line. These species reproduce predominantly or entirely by parthenogenesis—essentially a form of self-cloning—and the Y chromosome has been entirely lost in the population. This also ties into hybrid speciation because it is believed that these parthenogenic species arose from hybridisation between two or three sexual species 13 leading to polyploid individuals (i.e. those with ’extra’ sets of chromosomes).

For example, the all-female parthenogenic species Cnemidophorus neomexicanus is actually a hybrid of two sexual species, Cnemidophorus inornatus and C. marmoratus (or C. tigris, according to Wikipedia), and thus new individuals of this species can be formed either by parthenogenesis in a single C. neomexicanus parent, or sexual reproduction between a male and female C. inornatus and C. marmoratus/C. tigris.14 Some female parthenogenic species are also able to interbreed sexually with males from sexual species, resulting in hybrids which may or may not also be parthenogenic.15

Genus? Species?

So you can ask, “Well, what the fuck is a genus, or a species for that matter, if it doesn’t necessarily indicate whether two animals are genetically similar enough to interbreed or not?” And, more to the point, is there a strict set of quantitative criteria that defines whether two populations of organisms are classified as the same or different species? And I mentioned speciation, which brings up the question, when exactly in the process of evolution does one species actually become another?

The thing is, there aren’t actually definitive answers to these questions. If you ask a bunch of biologists what a species is, it’s likely you’ll get different answers. “Species” also has a number of definitions16 mainly depending on the type of organism being studied and the angle it is being studied from. For bacteria, for instance where “similar enough to reproduce” really isn’t applicable.

I think the general consensus is that individuals are grouped together if their genetic similarity to one another is 97-98% or higher, while a similar definition of “organisms that are highly genetically similar to one another” tends to be used for asexually reproducing organisms such as some plants, and parthenogenic animals like whiptail lizards or Bdelloid rotifers, which does of course raise the question of what exactly “highly similar” means—any decided-upon cutoff point will necessarily be somewhat arbitrary. Such groupings of organisms may be referred to as phylotypes to distinguish them from the reproductive definition of a “species”. 17

Likewise, a lot of ecological writing will define species and speciation according to reproductive isolation, which isn’t necessarily synonymous with reproductive compatibility—reproductively isolated populations may be genetically able to reproduce, but be prevented from doing so or unlikely to do naturally so due to differences in geographical location, habitat or behaviour (think lions and tigers).

These are some of the many different “types” of species, with either competing or overlapping definitions of what exactly constitutes a species in each case:

- Morphological or typological species (morphospecies)

- Phylogenetic species

- Evolutionary species

- Genetic species

- Genalogical concordance species

- Reproductive species

- Autapomorphic species

- Ecological species

- Recognition species

- Phenetic species

- Isolation species

- Cohesion species

…You get the idea.

For vertebrates, I think generally the two most used definitions are the biological species concept (BSC) and phylogenetic or cladistic species concept (PSC), which differ in their criteria for what they consider a species1819.

PSC, for example, doesn’t include a subspecies category while BSC does. Thus, some organisms that are classified as subspecies of the same species under BSC are either classified as different species or are lumped together as the same species under PSC. For example, grey wolves and domestic dogs. The domestic dog is/was often considered a separate species to the grey wolf, for obvious (morphological/behavioural) reasons—the wolf was Canis lupus, the dog C. familiaris—but since dogs are descended from wolves (a now-extinct lineage of wolves, not modern grey wolves20 but Canis lupus nonetheless) they are more properly classified as a subspecies, C. l. familiaris. Likewise, having also ultimately descended from wolves, the dingo is officially classified as C. l. dingo, although there is some debate about that. You can see why species boundaries and definitions can get murky, especially when the exact evolutionary origins of a particular animal are unknown or hotly contested.

In fact, canids as a whole are kind of a mess when it comes to phylogeny. How many species of wolf there are really depends on who you ask. Some populations traditionally classified as subspecies of the grey wolf, for example the Indian wolf (traditionally C. l. pallipes), the Himalayan or Tibetan wolf (traditionally C. l. chanco) and the Eastern wolf (traditionally C. l. lycaon) have been suggested instead to be classified as separate species—Canis indica, Canis himalayensis and Canis lycaon, respectively.2122

Of course these classifications aren’t set in stone, either - new studies and discoveries are constantly uprooting and rewriting our knowledge of phylogenetic and evolutionary relationships among species. Sometimes it’s also pretty much impossible to accurately represent the relationships between similar-but-distinct populations using only the terms “genus” and “species”, which is where alternate concepts like species complex, subgenus and superspecies come in.

Another feature of evolution and speciation that makes classification difficult is what are known as ring species, in which a series of neighbouring populations of organisms may evolve divergently (i.e. undergo allopatric speciation) in such a way that each geographically adjacent or overlapping population can interbreed with the next, but the last population in the “ring” has diverged to the point that it can no longer interbreed with the first (basically, population A can interbreed with population B, B with C and C with D, but D can no longer interbreed with A).23

When does the actual split occur, and at what point in the ring can we consider the populations to be different species? We just don’t know.

The point is, though, that there is no definitive, universally agreed-upon cutoff point at which we can say with certainty that two organisms have evolved sufficiently as to become different species, any more than you can definitively say where along a rainbow spectrum of colours red becomes orange or orange becomes yellow.

The decision whether to lump or split taxa becomes even more arbitrary in paleontology than it is with extant species when you’re working with an incomplete fossil record and pretty much going entirely on morphological similarities since genetic or molecular analysis often isn’t possible, there isn’t really a way to conclusively determine whether that specimen you found represents a new species, a new genus, or is simply a larger/smaller/juvenile/unfortunate-looking version of an already-described animal. Many specimens now believed to be juveniles of previously-described species were originally believed to be completely new ones.

Obviously, at the end of the day, a zebra is materially different from a dog in the same way that, to get back to the original topic, a penis is materially different from a vagina (actually a bad analogy since homologous reproductive organs are much more similar to each other than taxa that have been separated for millions of years, but anyway). The biological differences and similarities themselves exist, but any attempt to categorise and quantify them will necessarily rely on socially constructed and frequently arbitrary models, definitions and assumptions.

That’s basically what science is: a continuous (and frequently wildly inaccurate) attempt to try to make sense of reality. We often attempt to understand or make predictions about reality using mathematical or quantitative models of the situation or by sorting things into sets and categories, which is useful and necessary in many cases but is also often far too simplistic to be taken as any kind of gospel truth regarding the actual nature of reality. Simply put, reality doesn’t care for or abide by human-made rules and categories.

Essentially, we’re trying to find quantitative ways to represent things that are by nature qualitative, and that’s always going to be arbitrary to some extent. Obviously biological characteristics (whether genetic, sexual/reproductive, etc.) objectively exist and would continue to exist if humans and human culture were to suddenly disappear, and in that sense, things like sex, gender and taxonomic classification can be said to be based in biological reality. But human attempts to define or categorise these characteristics—for example species concepts, the binary model of sex, etc.—are not in themselves biological realities, and are subject to change based on new information. For example, evolutionarily speaking, “reptiles” (as we traditionally understand them) don’t exist.24

Obviously, this doesn’t mean that lizards, tortoises, snakes, crocodiles, non-avian dinosaurs etc. don’t exist or never existed. It simply means that the socially constructed classification of animals into two distinct, mutually exclusive groups called “reptiles” and “birds” is completely arbitrary and not actually the result of any inherent biological reality (in fact the opposite).

Conclusion

Highschool biology syllabus can’t be the only source of truth when it comes to gender and sex. It’s a lot more complex than that. Quoting Charles Darwin:

“From these remarks it will be seen that I look at the term species as one arbitrarily given for the sake of convenience to a set of individuals closely resembling each other, and that it does not essentially differ from the word variety, which is given to less distinct and more fluctuating forms. The term variety, again, in comparison with mere individual differences, is also applied arbitrarily, and for convenience sake.”25

Neither gender nor biological sex is innate, binary, or a scientific reality in any way, shape, or form; and the vast majority of biologists, scientists, doctors, psychologists, historians and anthropologists have been debunking these ignorant claims for decades and proving that both of these concepts are socially constructed. Since gender as completely subjective, nonbinary genders have existed since the dawn of human civilization, even dating back to Mesopotamia, the VERY FIRST human society, at that. There are many countries today where there are officially more than two genders recognized, and there are multiple languages that are entirely gender-neutral.

The gender binary itself is an entirely European theory based on a complete lack of understanding of science,

and was only recently forced on the world via colonialism, violence, and genocide.

Saying that nonbinary genders aren’t real is an act of transphobia, racism, and imperialism,

and is the same as saying that thousands of cultures around the world, millions of personal experiences,

and entire societal structures throughout history are not real, which makes no sense.

It is part of human nature and basic natural variation to not fit into oversimplified binary categories.

TNU

-

https://your-biology-is-wrong.tumblr.com/ and https://emo420.tumblr.com/ , both are no longer active. Thanks for sharing your knowledge. ↩︎

-

The Yogyakarta Principles address a broad range of international human rights standards and their application to SOGI issues. On 10 Nov. 2017 a panel of experts published additional principles expanding on the original document reflecting developments in international human rights law and practice since the 2006 Principles, The Yogyakarta Principles plus 10. The new document also contains 111 ‘additional state obligations’, related to areas such as torture, asylum, privacy, health and the protection of human rights defenders. The full text of the Yogyakarta Principles and the Yogyakarta Principles plus 10 are available at: www.yogyakartaprinciples.org [2022 Jul 14] ↩︎

-

Mallet, J. (n.d.). The speciation revolution. Blackwell Science LTD. http://www.ucl.ac.uk/taxome/jim/pap/malletjeb01.pdf ↩︎

-

Hey, J. (n.d.). The mind of the species problem. TRENDS in Ecology & Evolution. https://evolution.powernet.ru/library/Scienc6.pdf ↩︎

-

Mallet, J. Hybrid speciation. Nature 446, 279–283 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05706 ↩︎

-

Cohen, B. L., Baker, A. J., Blechschmidt, K., Dittmann, D. L., Furness, R. W., Gerwin, J. A., Helbig, A. J., de Korte, J., Marshall, H. D., Palma, R. L., Peter, H. U., Ramli, R., Siebold, I., Willcox, M. S., Wilson, R. H., & Zink, R. M. (1997). Enigmatic phylogeny of skuas (Aves:Stercorariidae). Proceedings. Biological sciences, 264(1379), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1997.0026 ↩︎

-

Kays, R. (2015, November 13). Yes, eastern coyotes are hybrids, but the ‘coywolf’ is not a thing. The Conversation. Retrieved July 14, 2022, from https://theconversation.com/yes-eastern-coyotes-are-hybrids-but-the-coywolf-is-not-a-thing-50368 ↩︎

-

Cornell University. (2006, November 30). Two Rapidly Evolving Genes Offer Geneticists Clues To Why Hybrids Are Sterile Or Do Not Survive. ScienceDaily. Retrieved July 13, 2022 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/11/061129150811.htm ↩︎

-

NBC Universal. (2005, April 15). Whale-dolphin hybrid has baby wholphin. NBC News. Retrieved July 14, 2022, from https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna7508288 ↩︎

-

Fankhauser, G., & Cumming, K. B. (2008). Snake Hybridization: A Case for Intrabaraminic Diversity. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism (Vol. 6, No. 1, p. 13). PDF copy here: https://www.icr.org/i/pdf/technical/Snake-Hybridization-A-Case-for-Intrabaraminic-Diversity.pdf ↩︎

-

Hartwell, S. (n.d.). Domestic x Wild Cat Hybrids. Messy Beast. http://messybeast.com/small-hybrids/hybrids.htm ↩︎

-

Kalla, D. J. U., Danladi, F. B., & Dass, U. D. (2008). Chicken Guineafowl Hybrid Produced Under Natural Mating. Nigerian Veterinary Journal, 29(2), 59–61. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/nvj/article/viewFile/3595/38131 ↩︎

-

Charles J. Cole, Harry L. Taylor, Diana P. Baumann, Peter Baumann “Neaves’ Whiptail Lizard: The First Known Tetraploid Parthenogenetic Tetrapod (Reptilia: Squamata: Teiidae),” Breviora, 539(1), 1-20, (5 December 2014) ↩︎

-

Cole, C. J., Dessauer, H. C., & Barrowclough, G. F. (1988). Hybrid Origin of a Unisexual Species of Whiptail Lizard, Cnemidophorus neomexicanus, in Western North America: New Evidence and a Review. America Museum Novitates, 1–38. ↩︎

-

Christiansen, J. L., Degenhardt, W. G., & White, J. E. (1971). Habitat Preferences of Cnemidophorus inornatus and C. neomexicanus with Reference to Conditions Contributing to Their Hybridization. Copeia, 1971(2), 357–359. https://doi.org/10.2307/1442858 ↩︎

-

A list of 26 Species “Concepts” | ScienceBlogs. (2006, October 1). ScienceBlogs. Retrieved August 13, 2022, from https://scienceblogs.com/evolvingthoughts/2006/10/01/a-list-of-26-species-concepts ↩︎

-

Moreira, D., López-García, P. (2011). Phylotype. In: , et al. Encyclopedia of Astrobiology. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-11274-4_1210 ↩︎

-

Mallet J. (2010). Group selection and the development of the biological species concept. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 365(1547), 1853–1863. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0040 ↩︎

-

Wheeler Q. D. (1999). Why the phylogenetic species concept?-Elementary. Journal of nematology, 31(2), 134–141. ↩︎

-

Skoglund, P. (2015, June 1). Ancient Wolf Genome Reveals an Early Divergence of Domestic Dog Ancestors and Admixture into High-Latitude Breeds. Current Biology. Retrieved August 13, 2022, from https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(15)00432-7 ↩︎

-

Aggarwal, R. K., Kivisild, T., Ramadevi, J., & Singh, L. (2007). Mitochondrial DNA coding region sequences support the phylogenetic distinction of two Indian wolf species. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research, 45(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0469.2006.00400.x ↩︎

-

Kyle, C., Johnson, A., Patterson, B., Wilson, P., Shami, K., Grewal, S., & White, B. (2006). Genetic nature of eastern wolves: Past, present and future. Conservation Genetics, 7(2), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-006-9130-0 ↩︎

-

Martins, A. B., de Aguiar, M. A. M., & Bar-Yam, Y. (2013). Evolution and stability of ring species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(13), 5080–5084. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1217034110 ↩︎

-

Lawton, G. (2011, May 18). Rewriting the textbooks: No such thing as reptiles. New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg21028132-500-rewriting-the-textbooks-no-such-thing-as-reptiles/ ↩︎

-

Darwin, C. (n.d.). The Origin of Species: Chapter 2. The TalkOrigins Archive. https://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/origin/chapter2.html ↩︎